Understanding Intersectionality

See also: Understanding OthersIntersectionality is the idea that discrimination and oppression do not happen through a single lens. Instead, all of us have multiple characteristics that affect how we are seen and treated by others. Individuals therefore experience discrimination and bias in a unique way, depending on their combination of characteristics. Our individual characteristics also influence and affect each other in different ways.

The term was coined by academic and lawyer Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989. It remains crucial and relevant today. We see its effects in the way in which certain groups become poorer and more marginalised across generations. We can also use the concept to understand better how to address inequalities in society.

Defining Intersectionality

There are several definitions of intersectionality, but it is worth going back to Kimberlé Crenshaw’s work for a definitive version. In an interview published in Time magazine in 2020, she explained:

“It’s basically a lens, a prism, for seeing the way in which various forms of inequality often operate together and exacerbate each other.”

She also provided a metaphor to help others to understand it more clearly (see box).

A metaphor for intersectionality

“Racism road crosses with the streets of colonialism and patriarchy, and ‘crashes’ occur at the intersections. Where the roads intersect, there is a double, triple, multiple, and many-layered blanket of oppression.” - Kimberlé Crenshaw

The point is that we often think about ‘reducing gender inequality’ or ‘reducing racial inequality’. However, we tend to miss the point that some people experience both—and that their experience is not simply ‘gender inequality + racial inequality’.

It is also important to note that your personal characteristics do not just provide barriers to access to good things. For some people, they provide better access. This is known as privilege.

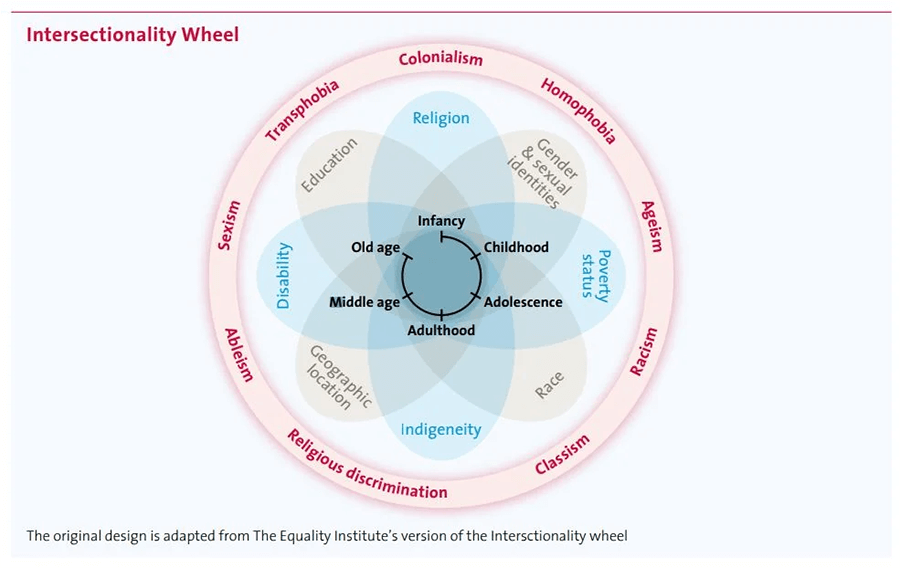

There are many factors that may affect our access to resources (see diagram)—and they come together in different ways for different people.

It is not simply a matter of adding up advantages and subtracting the disadvantages. Instead, inequalities are related in a more dynamic way, and are also dependent on time and location.

Source: UN Women Australia

The Importance of Intersectionality

Why does the idea of intersectionality matter?

Partly, it matters because we tend to bring our own experiences to bear when we see a problem or issue. We say things like,

“Well, I’m a woman, and I’ve never experienced that, so I’m not sure why you’ve had that experience.”

Or

“But [Name] is Black, and he hasn’t had this problem.”

[Implication: I’m not sure I believe you because my experience is different]

However, the idea of intersectionality also matters on a global stage and scale.

Without a good understanding of what it means and how it operates in practice, we may approach global issues in the wrong way.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals are designed to eliminate world poverty by 2030. However, achieving them requires an understanding that certain groups are disproportionately affected by lack of equity because of a series of underlying social issues. It is worth looking at some examples.

1. The effect of ‘environmental racism’

Black people in the USA are 75% more likely than white people to live near the boundaries of chemical facilities.

This means that any leaks or pollution from these facilities—and let’s face it, these happen—are disproportionately likely to affect Black people.

Worse, many of these chemicals are linked to birth defects, cancers and other chronic illnesses. This therefore means that these communities are more likely to have high levels of conditions that mean that they need more healthcare—a major financial issue in the USA—and less able to work. This builds a cycle of disadvantage that spreads across generations.

2. The effect of forced marriage

Young women in developing countries, and especially in poorer populations, are particularly vulnerable to being forced to marry when they are still legally children.

These girls are less likely to have access to contraceptive choices, or good healthcare. They are therefore more vulnerable to health problems during pregnancy and afterwards, and to domestic violence and abuse. They are also less likely to be able to be fully economically active. Their daughters are also likely to experience forced marriage when they, in turn, reach their teens.

3. The effect of disabilities and chronic illnesses

People with disabilities and chronic illnesses are significantly less likely to be able to work full-time.

They may need more allowances in the workplace, which employers may be reluctant to offer, or which may be impossible to provide. The unpredictability of their condition may simply mean that they cannot reliably work. They therefore have smaller household incomes. In the USA, this also means that they are less likely to have good health insurance coverage—but will often have bigger medical bills.

In all these cases, a specific disadvantage is compounded by other, related issues that make it harder to overcome the original problem.

“There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.”

Intersectionality in Practice

The United Nations has outlined eight ‘enablers’ of intersectionality. They are designed for policy makers and those tackling big global problems. However, they are also a helpful way of considering your own prejudices and biases in the context of intersectionality. They are:

-

Reflexivity. The ability to examine your own beliefs (and therefore biases and prejudices) and how these might influence how you work with others. There is more about this in our pages on Reflective Practice and Unconscious Bias.

Dignity, Choice and Autonomy. The ability to respect and uphold the dignity, choice and autonomy of others. You cannot take on someone else’s dignity or autonomy for them. You should also not make choices for anyone without fully consulting their wishes. We might see this translate into consulting people from minority groups, and not simply assuming that you know how best to ‘do’ things for them.

Accessibility and ‘universal design’. Making reasonable changes or accommodations to ensure that everyone has access to resources and rights, and to reduce or remove barriers to participation. For example, it is good practice to ask people what they need to help them participate, not to assume that you know. The principle of ‘universal design’ means designing things to be usable by as many people as possible without further adaptation.

Drawing on diverse sources of knowledge. This means seeking out people with new knowledge, especially those who are not typically regarded as ‘experts’, to learn from them. The question to ask here is ‘Who has not been consulted?’

Intersecting identities. Considering how different identities or characteristics come together in an individual, and what social effects this might create. This needs to be a dynamic and ongoing process, because identities are not static, and neither are their effects.

Relational power. Power is not an absolute. You might hold power in one relationship, but not in another. Consider, for example, the man who is at the bottom of the organisational hierarchy at work, but then goes home and shouts at his partner or children. Questions to ask are about who can make decisions, and who is accountable.

Time and space. Relationships between characteristics are not static. They change over time, and in different locations. Both privilege and disadvantage can increase and decrease under different circumstances.

Transformative and rights-based approach. This is the idea that you have to change your approach to make a difference. Look at both resources and relationships to ensure that they are driving change and better support human rights.

Warning! Keep it human

Intersectionality is often described as a framework for analysis of individual situations. However, this level of formality risks reducing individuals to “collections of socio-demographic characteristics”, rather than seeing them as fully rounded people. It is therefore important to guard against this risk, and recognise that we are all people, with unique experiences.

A Final Thought

Much of what is included on this page may sound like common sense, or ‘treating people right’.

Indeed, much of it is simply about ‘treating people right’. However, it is good to be reminded that everyone’s experience is unique. Just because you have experienced barriers does not mean that you understand someone else’s experience of those barriers—and nor should you assume that.